By Carol McCrite

Note: This story was originally published in the historical book The Way We Were – Recollections of South Walton Pioneers by South Walton Three Arts Alliance. Republished with permission.

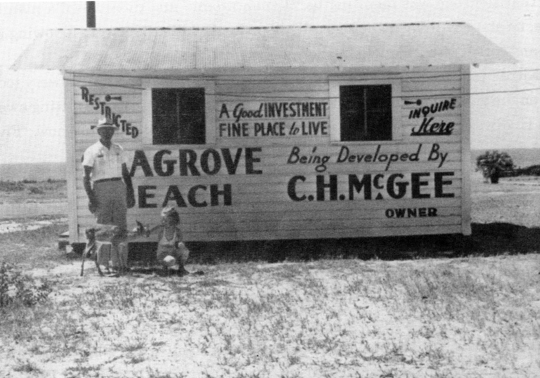

“Seagrove Beach – Where Nature Did Its Best.” C.H. McGee, Sr. (known to friends as McGee) coined the phrase to describe his personal feelings about the magnificent piece of gulf front land he purchased from J.R. Moody in 1949.

The 18-month campaign to acquire 160 acres of pristine beach in South Walton County became a monthly ritual for McGee and his son, Cube, as the drove to Mr. Moody’s Redhead, Florida farm, ate a wonderful home-cooked meal and “sat a spell.”

Then came the inevitable question: “Well, Mr. Moody, are you going to sell me Seagrove?” Predictably, the answer would always be, “Mr. McGee, let me think about it for a few days.”

Persistence paid off when Mr. Moody finally acquiesced with, “Yep,” and the deal was consummated for $75,000.

McGee was not the first man to look from afar at Seagrove land and envision it a virtual paradise. Civil War sailors used this stretch of coastline as a navigational point, labeling it the Green Hill. The evident beauty of scrub oak trees growing to the edge of a 45-foot bluff could be seen for at least a mile out at sea.

Seagrove was so remote, and far removed, it took a visionary like McGee to appreciate what it could become. Cube recalls thinking, “this will be a lot of work,” but he believed his Dad was the man who could accomplish that feat.

McGee’s target selling point billed Seagrove as the only beach with shoreline trees on the Gulf of Mexico’s highest bluff. Never mind there were no paved roads, no houses, no post office, no telephones, no medical services, and no restaurant. The newly-found paradise left its calling card on McGee’s heart, and he began a letter campaign describing Seagrove as a remote, quiet, getaway place where the only familiar sounds were those of whip-o-wills or waves kissing the shore.

Along his 2,640 feet of coastline, McGee built five houses, four to the east of Seagrove/Point Washington Road (now CR395). The county promised a paved road from Highway 98 – soon.

Because he saw what happened to other coastal developments, McGee incorporated covenants and restrictions to protect Seagrove. He wanted it to be a nice place to bring families on vacation, so he carefully planned for the future. Tourists were soon attracted to this hamlet nestled 45 feet above sea level. A store McGee built (now Seagrove Village Market) furnished visitors with the barest of necessities. Casey’s Ice House in Freeport kept wood boxes full and mail cam regularly – to the Point Washington Post Office. Even newspapers were dropped out on the corner of Highway 98.

Until telephone service began in September of 1958, Mr. Alfred Barrett happily delivered phone messages to Seagrove for $5.00 a message. His one-stop filling station-grocery, located on Highway 98 a mile east of the road to Seagrove, housed the only telephone. Emergencies such as the need for a doctor in the middle of the night necessitated Cube’s getting dressed and driving to Mr. Barrett’s. These inconvenient trips highly motivated Cube to go to Tallahassee to appear before the Public Service Commission.

The Tri-Cities Telephone Company system jammed the first day service began because “everyone was using the phone,” Cub recalls. “Complaints poured in from ‘I ordered a wall phone,’ to ‘my phone doesn’t work properly.’ Most of use would have climbed a pole just to make a call, but newcomers were just not aware of how desperate we were for service.

Applications to receive telephone service were quickly revised to read: “Under no circumstances call Mr. McGee unless it is for new service.” That same statement appeared in the phone book which, in reality was a card with 15 or 16 subscribers names listed alphabetically.

Wallace Barber, the one and only repairman did not wait for a formal request, but if anyone flagged him down, he would follow them home and repair their telephone on the spot.

Water furnished each Seagrove resident came in the form of a windmill-powered well that stood behind the little store. “We charged $3.00 a month no matter how much was used,” Cube recalls. “The problem was everyone got leaks but hardly anyone go the leaks repaired. A great number of people abused the system so we changed it by installing meters. Everyone was hopping mad. Later we were forced to raise the base to $4.00. Then Seagrove became a plumber’s heaven. Everyone wanted the leaks fix immediately,”

The Seagrove Road had it way with cars and trucks. Avee White of Point Washington was frequently called to come dig them out. It was a relief when, in 1950, the road was finally paved all the way to Highway 98. A dirt road running parallel to the beach was stopped on either end by Eater and Western Lakes. As late as 1969, people drove to Highway 98 then west to CR283 to get to Grayton, or else they climbed into a four-wheel drive and went straight down the beach.

By 1979, things began to change. The Birmingham News reported signs of significant growth. “The year-round residents of Seagrove sometimes wonder when Florida’s exploding beach development will catch up with them. Three new homes have sprung up in the last two years and some regard that as an ominous sign.”

McGee’s dream is now a reality. His vision, a beautiful vacation spot where families come and leave their troubles and cares behind is fulfilled.

“I am most proud that Dad has such foresight – that he planned for the future of Seagrove so well,” Cube says. Then he pauses to listen to the sound of waves kissing the shore and the call of a distant whip-o-will. With out a doubt, Seagrove Beach is where nature did its best.”

SIDEBAR:

Cube McGee passed away after this story was written. His home on the beach was torn down in 2014. However, his mother’s former home still stands on Grove Ave. along with several other block homes that remain along the beach in Seagrove.

Long time resident and owner of 30A Realty, Alice Forrester remembers the McGee’s fondly; she worked with Cube for 11 years.

“McGee believed in a sense of community, and there was a beach access at the end of just about every street,” Forrester said.

According to the Visit South Walton, Linda McGee Wright and Cube McGee donated four beach accesses for community use and approximately 750 feet of beachfront property within the neighborhood of Seagrove − #26 Nightcap; #27 Live Oak; #28 Hickory and #29 Dogwood/Thyme – on April 21, 1953 and officially donated the property to Walton County on Aug. 26, 2014. Each access is five feet wide and 150 feet long.

On April 23, 2015 Visit South Walton hosted a plaque dedication ceremony to commemorate Linda McGee Wright and Cube McGee.